Por Lorena Jiménez

Vanesa tenía apenas 24 años en su primer agresión sexual en el Metro de la Ciudad de México en 2003. Han pasado 21 años desde entonces. Mientras tanto…en la época actual, 2024, a sus 25 años Renata no solo comparte la misma experiencia, si no que comparte haber sufrido del mismo modus operandi en el que sus agresores, después de masturbarse, mancharon la ropa de Vanesa y Renata, elevando la agresión a otro nivel.

En la Ciudad de México, un 2.8% de mujeres usuarias constantes del transporte público han presenciado a lo largo de su vida este mismo episodio, según la Encuesta sobre la Violencia Sexual en el Transporte y otros Espacios Públicos en la CDMX de la ONU Mujeres.

De acuerdo con las cifras registradas por el Metro de la CDMX, el total de pasajeros que ingresaron a sus instalaciones en el 2022 fue de 1,057 millones 461 mil 875 usuarios, por otra parte, el Estudio origen-destino 2017 realizado por el Gobierno de la CDMX, contabilizó 7.91 millones de mujeres viajando en el metro.

A pesar de que los vagones exclusivos para mujeres en el metro existen desde 1970, la saturación en los andenes, orillan a las mujeres a abordar vagones mixtos en los que historias como las de Vanesa o Renata, quienes se dirigían a sus trabajos, son cotidianas.

Debido al aumento de las denuncias sobre acoso y violencia de género en el metro de la Ciudad de México, las autoridades han tomado medidas como la implementación de espacios exclusivos para mujeres y campañas de sensibilización, sin embargo las agresiones siguen siendo un tema de preocupación.

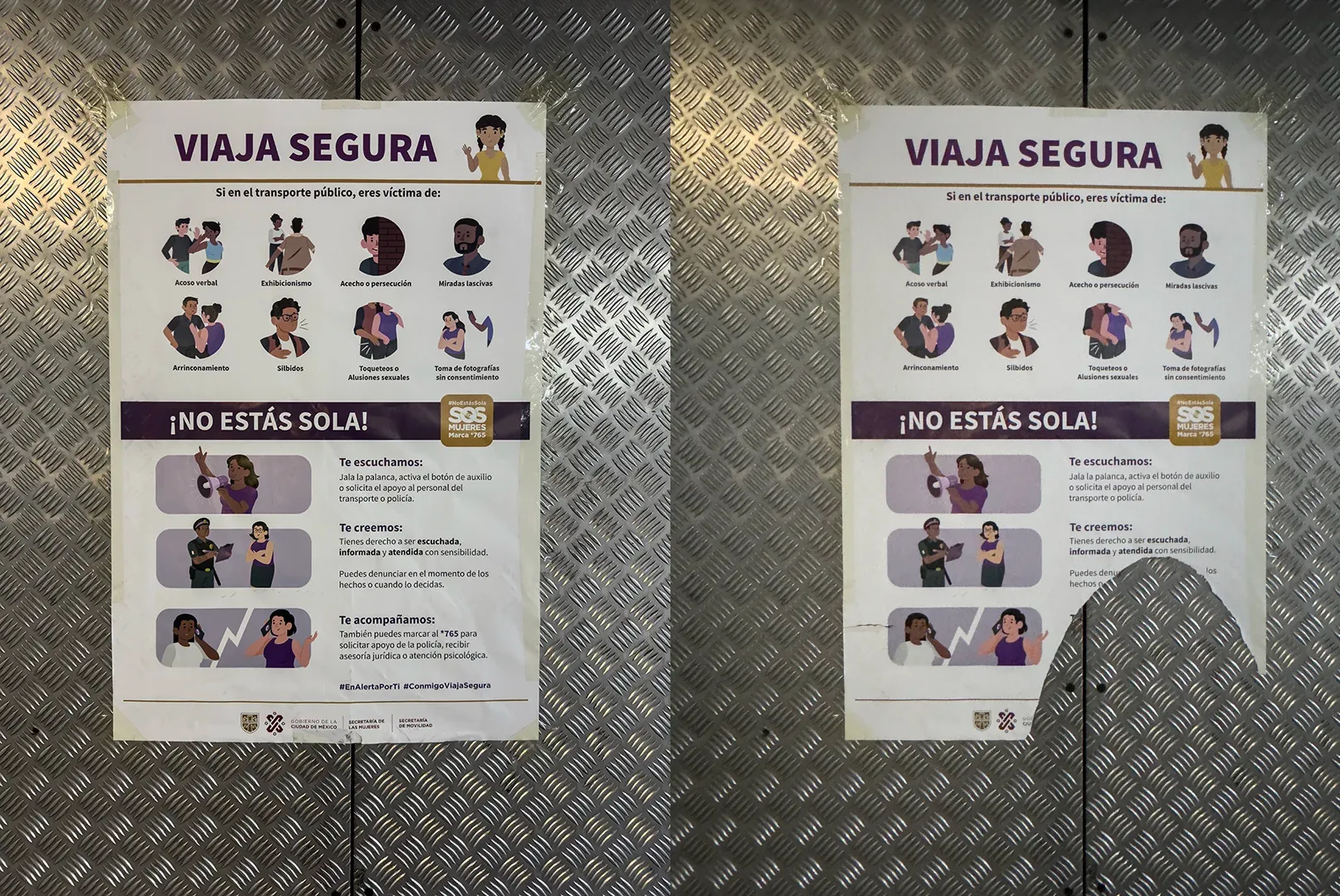

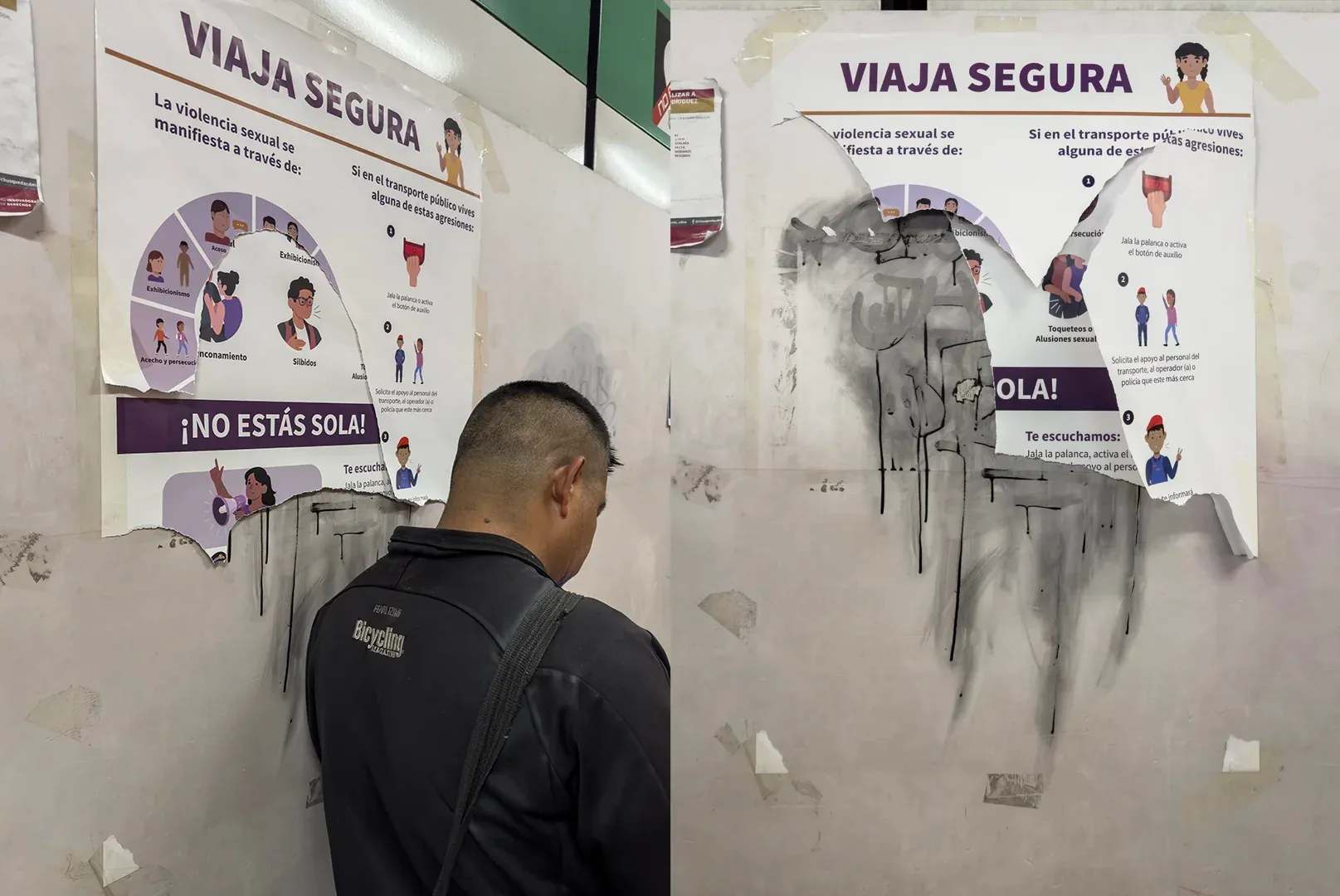

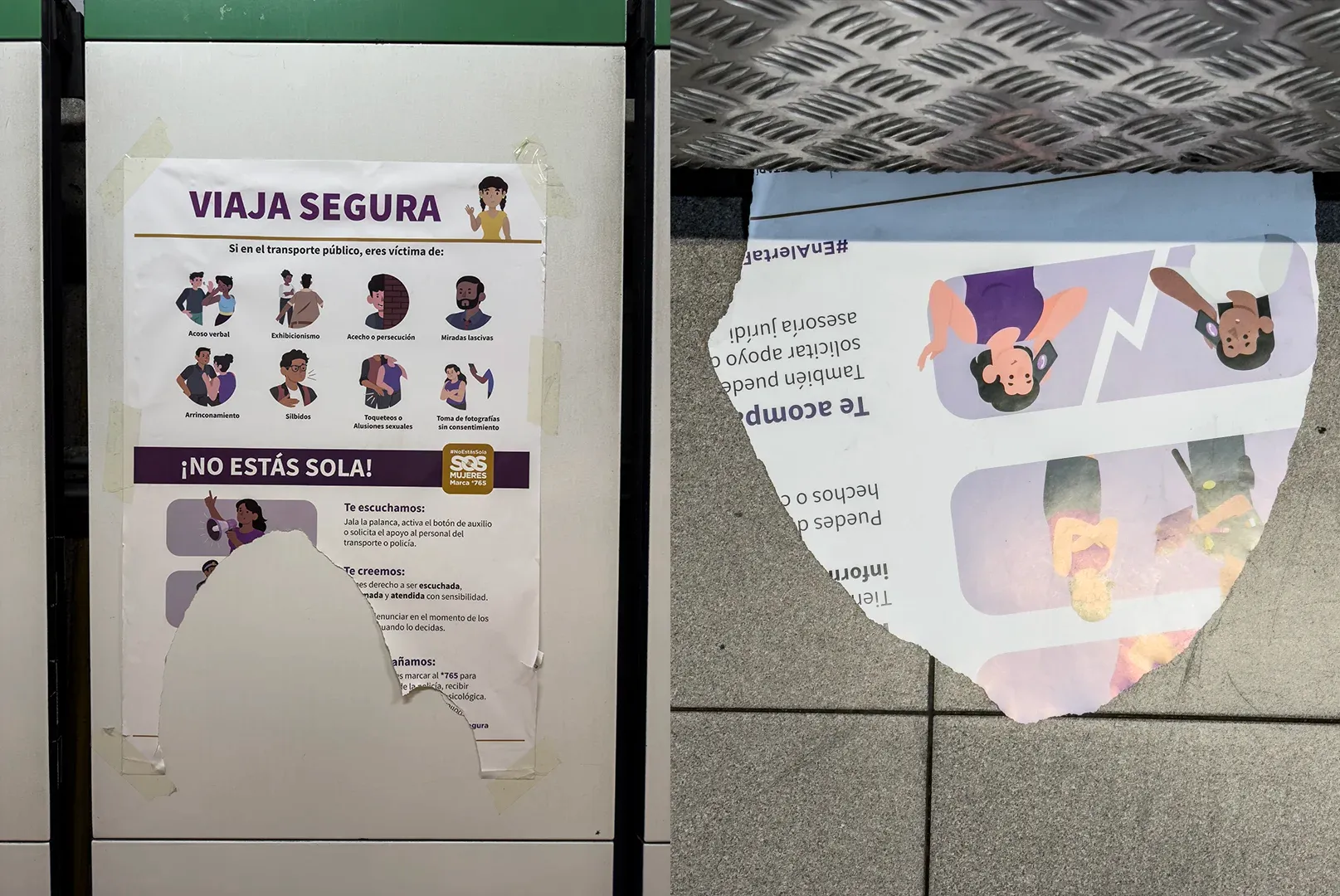

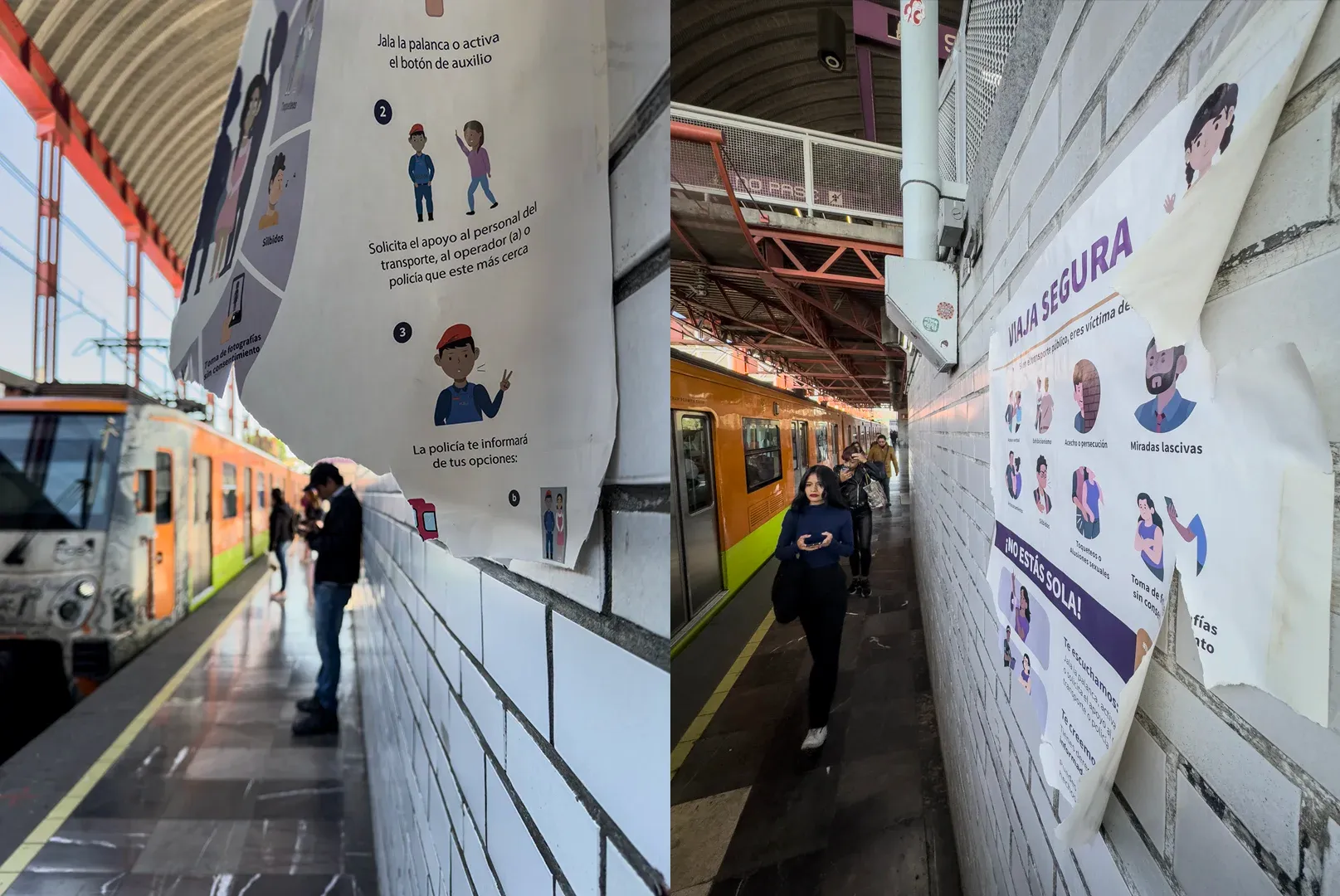

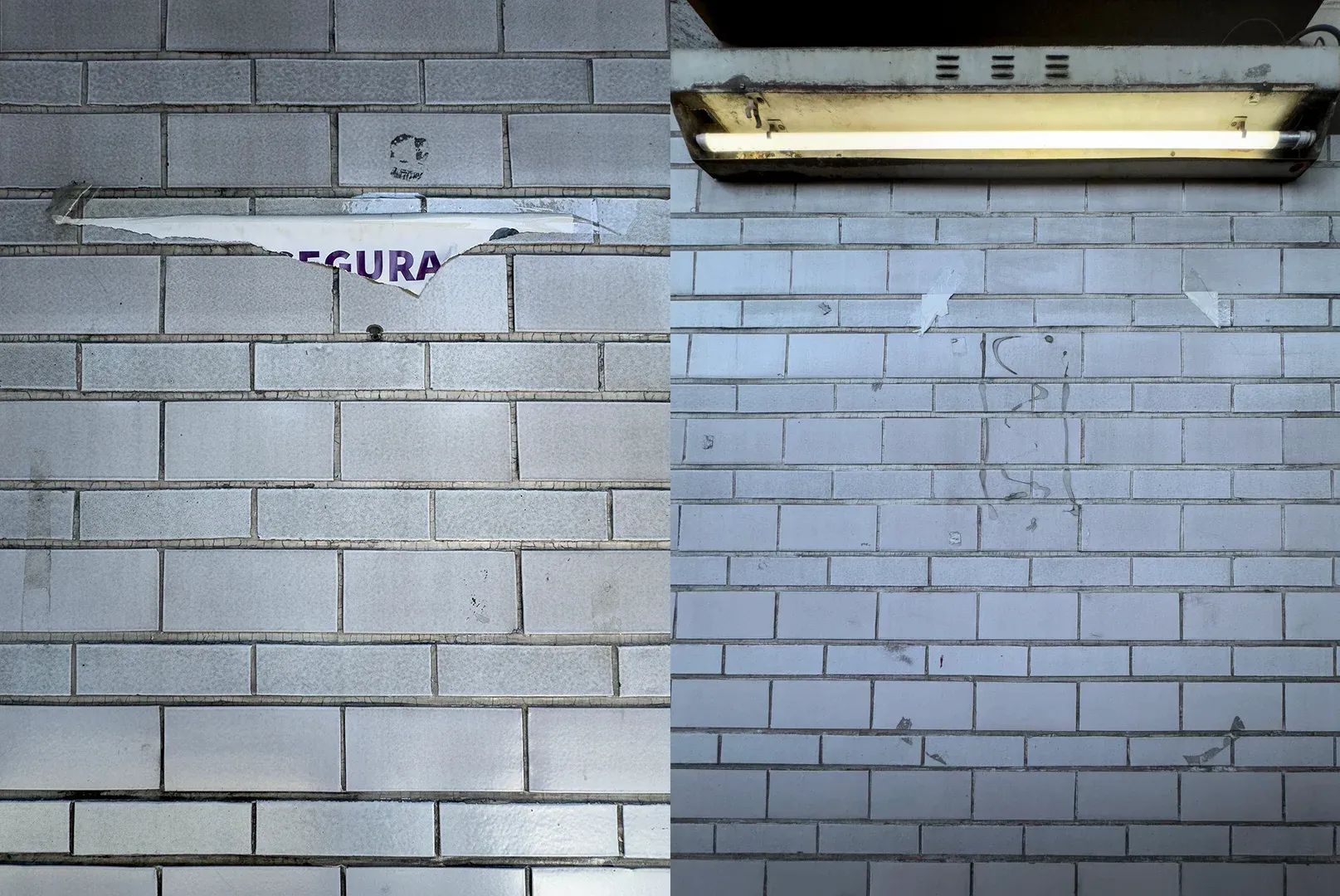

La línea 8 del metro es una de las que más concentra daños a los carteles de la campaña Viaja Segura. Estación Bellas Artes de la línea 8. Fotos: Fernando Luna Arce

La campaña Viaja Segura es una de las iniciativas que surgió desde 2008, cuyo esfuerzo se focaliza en nombrar las expresiones de violencia de género e informar sobre las formas en las que las autoridades pueden brindar apoyo a las mujeres víctimas de violencia sexual.

Desde hace un mes, en el Metro, una serie de carteles impresos en papel comenzaron a mostrarse en las instalaciones, sin embargo, pocos son los que sobreviven, algunos apenas son el rastro de lo que algún día fueron, quedando solo las orillas a la vista adheridas con cinta.

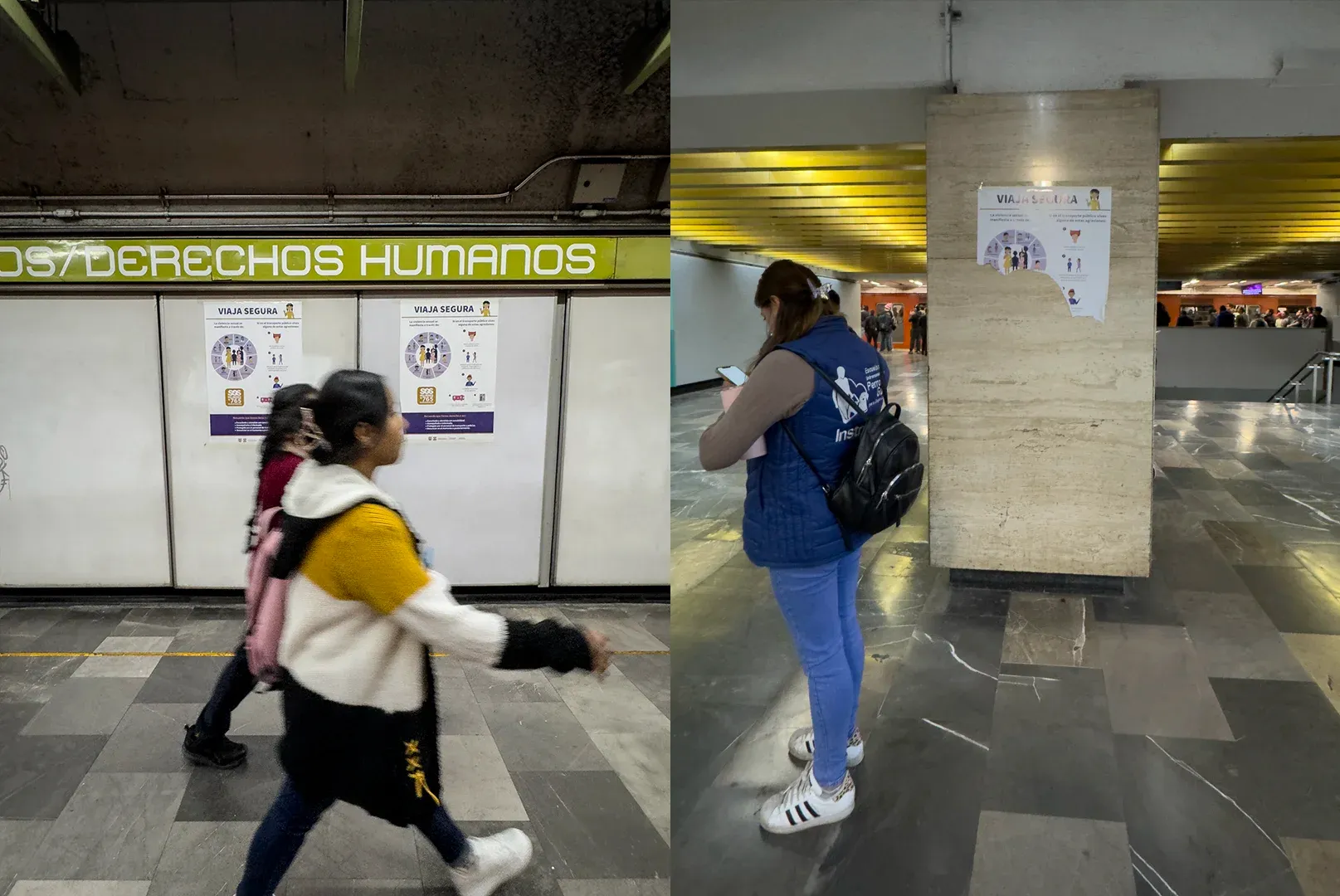

Un ejemplo de este fenómeno recorre la línea B, en la que de 21 estaciones, solo 4 tienen carteles en los andenes.

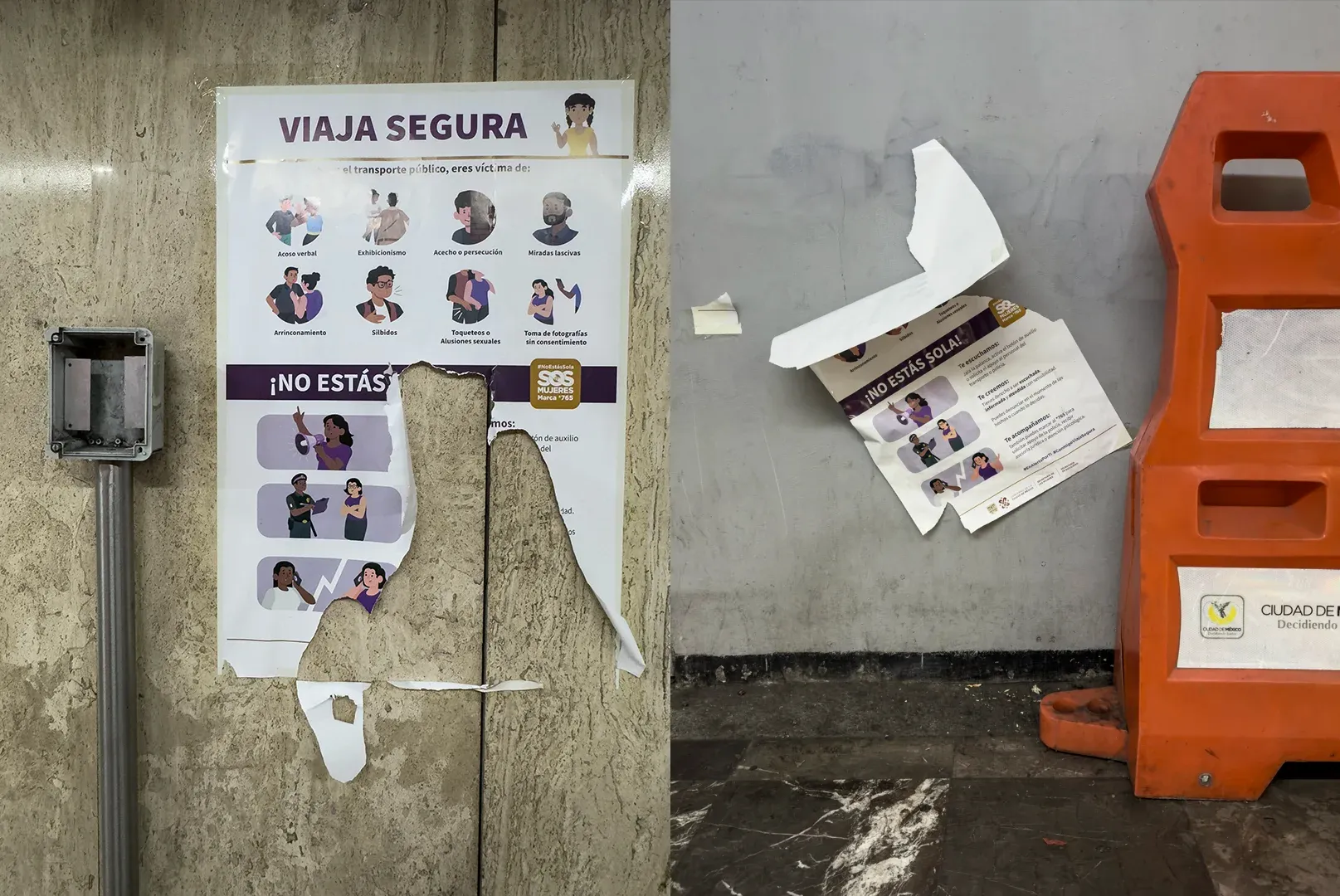

En cuanto a los carteles que recorren la Línea A, éstos encontraron otro destino diferente al de informar a los usuarios, pues la mayoría de los de la campaña fueron destruidos y desaparecidos.

Estaciones del Metro Santa Anita, Iztacalco e Iztapalapa. Fotos: Fernando Luna Arce

De acuerdo con cifras del Metro, Pantitlán, que forma parte de la Línea A, coronó como la estación con mayor afluencia en el 2020, con un promedio de 91,504 usuarios.

En entrevista con Edith Olivares Ferreto, directora Ejecutiva de Amnistía Internacional Sección Mexicana, platicamos sobre la importancia de cualquier esfuerzo de prevención de la violencia contra las mujeres y reconoció que como campaña es útil, particularmente en un país como México en donde las cifras de violencia contra las mujeres van al alza y el transporte público es un lugar de riesgo para las mujeres.

“Es muy importante que estas campañas estén vinculadas con acciones de acceso a la justicia, porque de lo contrario, el Estado pierde legitimidad cuando realiza estas campañas. Cuando vemos un cartel como este y luego las mujeres salen del metro porque han sido atacadas sexualmente y van a denunciar y tienen que invertir ocho horas de su día esperando a que les recojan la denuncia y además reciben maltrato de las autoridades o violencia institucional, se va perdiendo legitimidad y credibilidad del gobierno”.

Solo hasta que solicitamos una entrevista con algún miembro de vocería del Metro se pronunciaron respecto a estos carteles mediante una tarjeta informativa que nos entregaron.

“En relación a los carteles alusivos a Viaja Segura que se encuentran en mal estado, el Metro exhorta al público usuario a respetar el material impreso distribuído, tanto en estaciones como en trenes”.

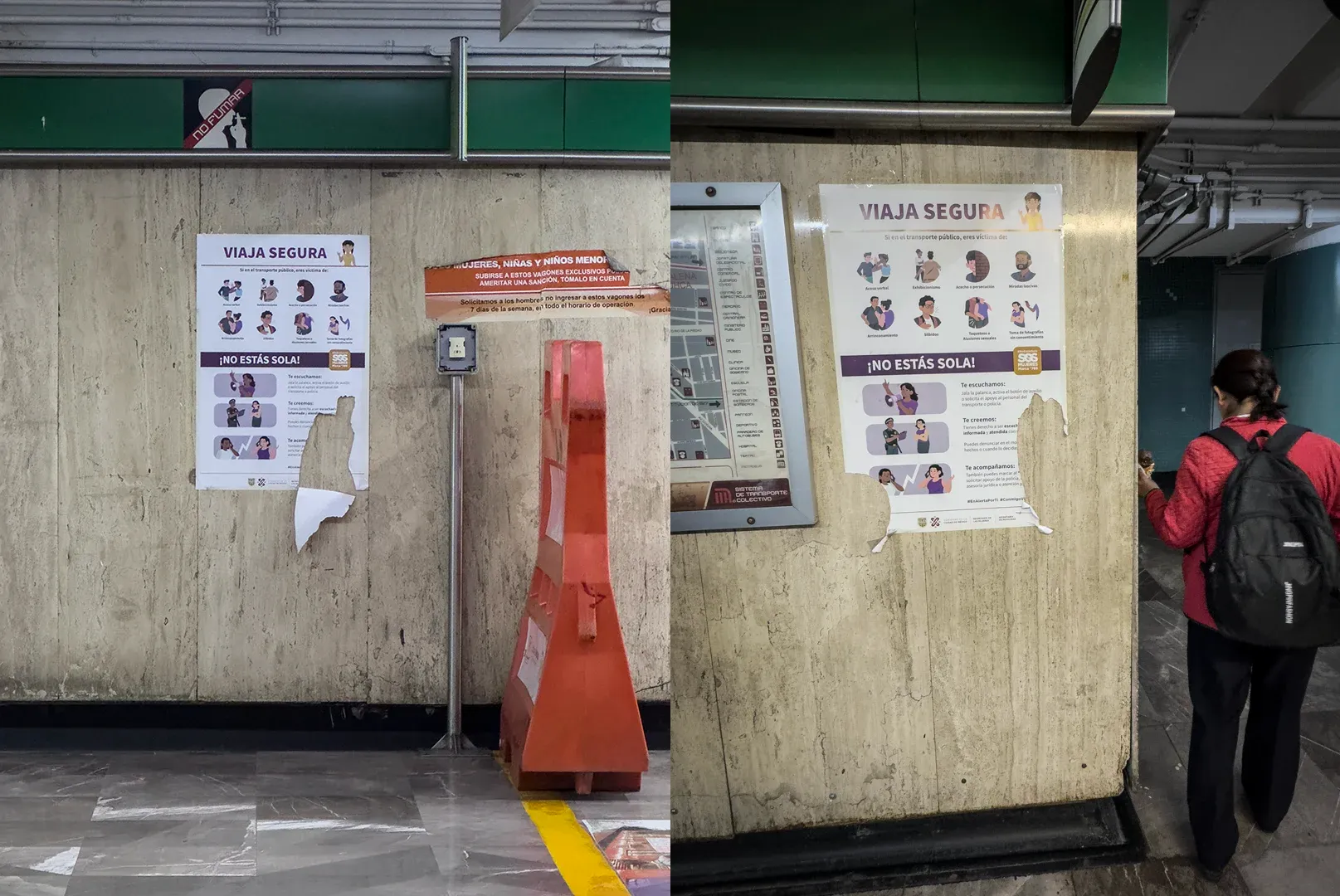

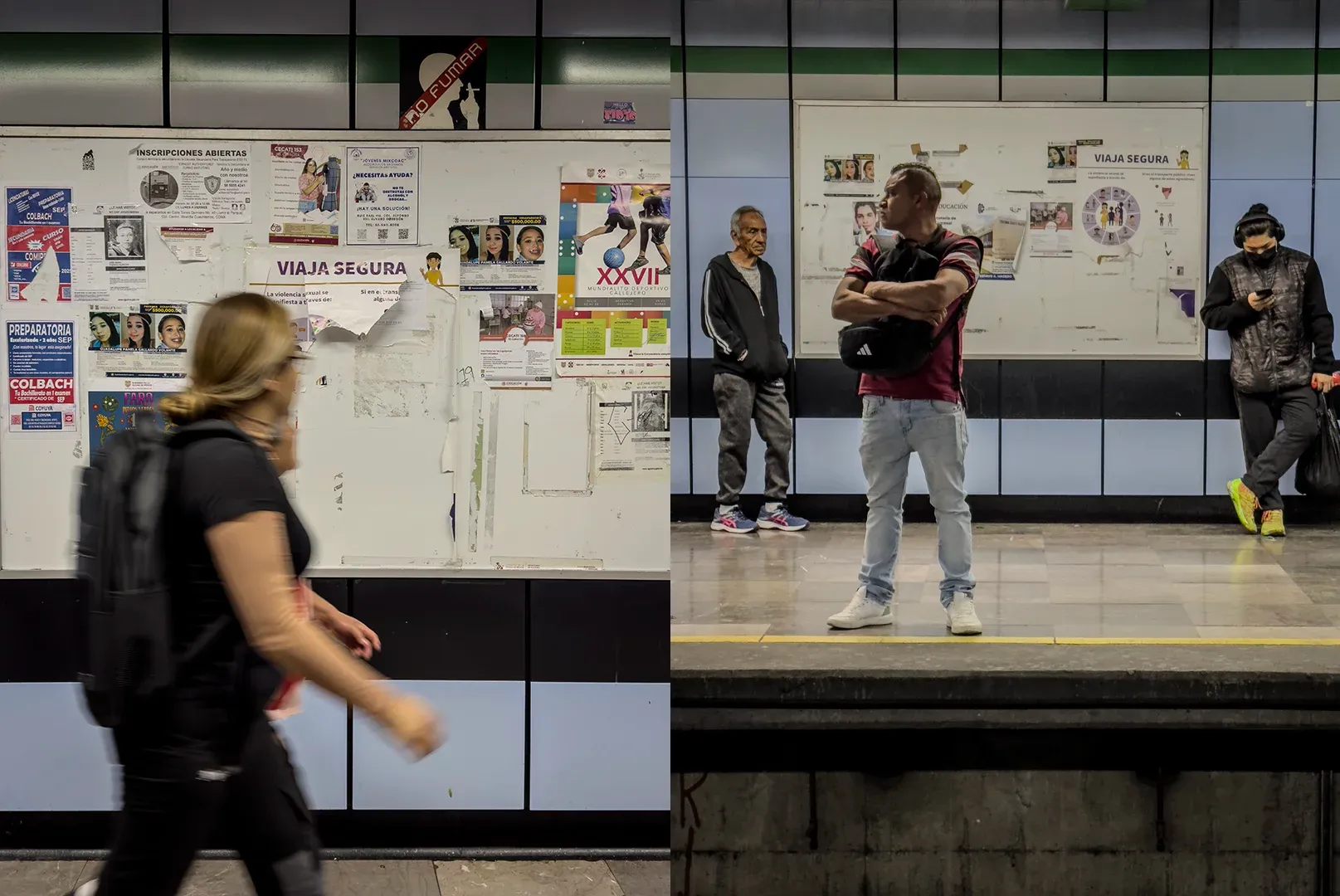

Estaciones Cerro de la Estrella, Constitución de 1917, San Juan de Letrán. La linea 6 presenta poco daños en los carteles salvo en la estación Martín Carrera. Fotos: Fernando Luna Arce

Vanesa, de ahora 45 años de edad, asegura que este tipo de campañas no existían cuando ella sufrió de violencia sexual en los vagones del metro, asegura que al salir del vagón “ni siquiera había un policía” y que actualmente, este tipo de campañas como Viaja Segura hubiera sido de ayuda para ella hace 21 años.

“Yo recibí ayuda hasta que llegué al hospital en el que trabajaba, en donde Lupita, la señora de la limpieza, me ayudó a resguardarme para poder lavar mi pantalón y horas después mi novio, y ahora esposo, me llevó un pantalón nuevo para que yo estuviera más cómoda”.

En cuanto a Renata, el acompañamiento que recibió, fue de otra mujer que le ayudó a conseguir transporte privado, Uber, para que pudiera llegar bien a su casa. Su decisión fue no denunciar ni acudir a ningún policía que estaba presente en el andén.

Actualmente, la Secretaría de Seguridad Ciudadana asignó a 5,800 elementos en las 195 estaciones del metro.

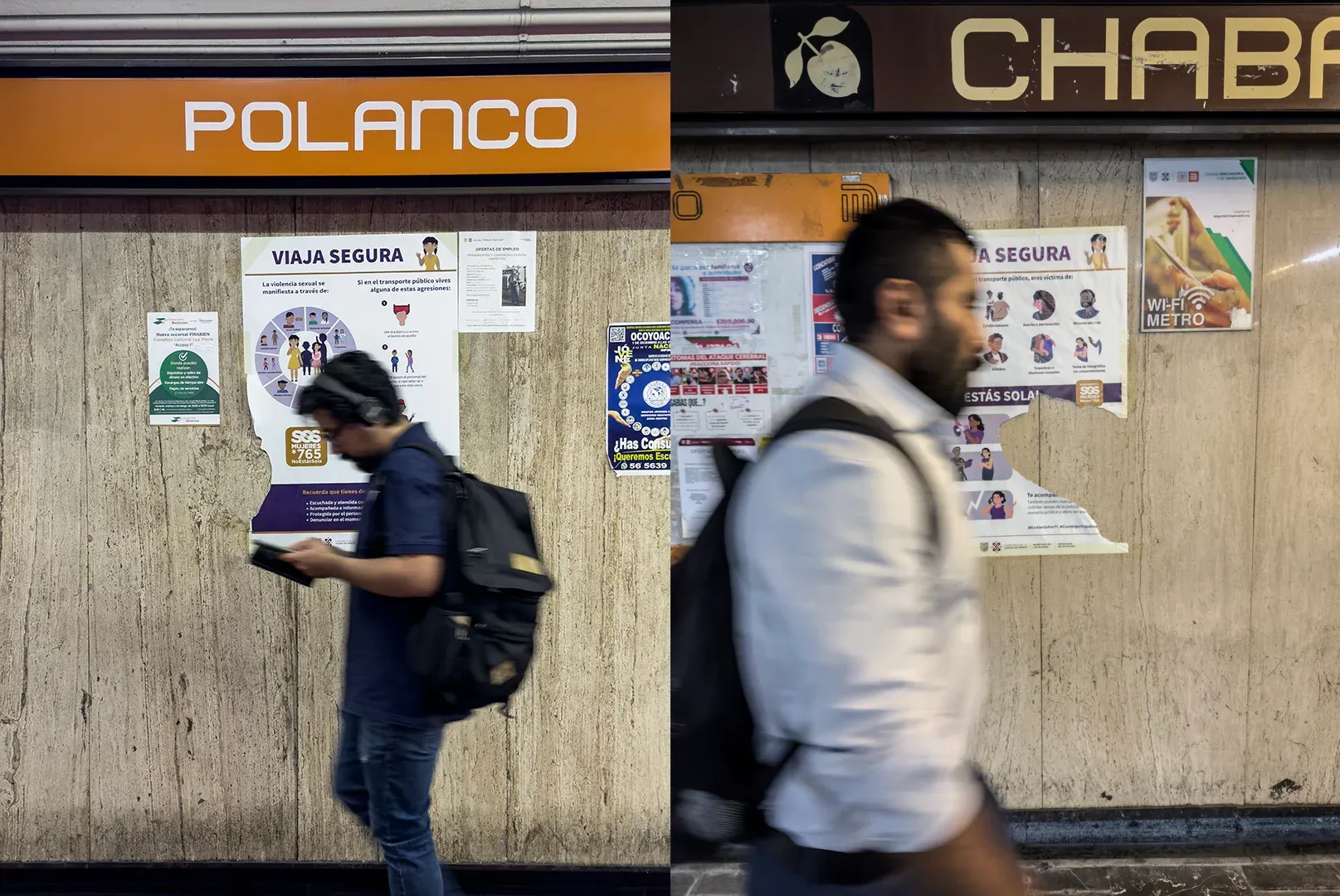

La línea 3 del Metro tiene muy poco carteles y están en buen estado, salvo la estación Zapata. La línea B de metro no hay carteles en los andenes con excepción del metro Tepito y estos están dañados. Fotos: Fernando Luna Arce.

En uno de los carteles de esta campaña, además de proporcionar el número *765 para recibir acompañamiento legal y psicológico, aseguran que de ser víctima de violencia sexual en el metro, un policía te brindará dos opciones: 1. Si no deseas denunciar, te acompañarán para terminar tu viaje, 2. Si deseas denunciar, te acompañarán a la Fiscalía de Delitos Sexuales o al Juzgado Cívico.

Sin embargo, pocos son los posters que sobreviven en las mamparas o en los andenes; quizás, la razón por la que algunos están intactos, es porque están al final del andén, donde nadie los ve, o al lado de las taquillas, cerca de los policías o del personal del Sistema de Transporte Colectivo.

Edith Olivares Ferreto asegura que lo que han observado desde Amnistía Internacional es que en México es que estas políticas se orientan a combatir la violencia contra las mujeres y poco en la sanción, es decir, son políticas que están concentradas en atender a quienes ya fueron violentadas y no tanto en la prevención.

“Desafortunadamente, el Estado mexicano sigue teniendo una deuda contraída con las mujeres, hay que continuar lanzando estas campañas y continuar haciendo estas acciones hasta que esto deje de suceder, que justamente, la gente deje de arrancar este tipo de carteles”.

El caso extremo de la línea B donde la mayoría de los carteles han desaparecido. Fotos: Fernando Luna Arce.

En el metro, viajar segura es tan difícil como hacer que estos carteles no desaparezcan. Al ver estas imágenes, existen dos posibilidades; la primera es que por accidente, los usuarios, al recargarse en las paredes, rompan estos carteles, o que estemos ante otra de las expresiones de violencia contra las mujeres: la privación del acceso a la información para la sanción de violencia sexual con la finalidad de que el destino de nuestros agresores en el metro, sea permanecer impunes.

*Lorena Jiménez hace videoarte y es periodista basada en la Ciudad de México.

Las opiniones expresadas son responsabilidad de sus autoras y son absolutamente independientes a la postura y línea editorial de Opinión 51.

Comments ()