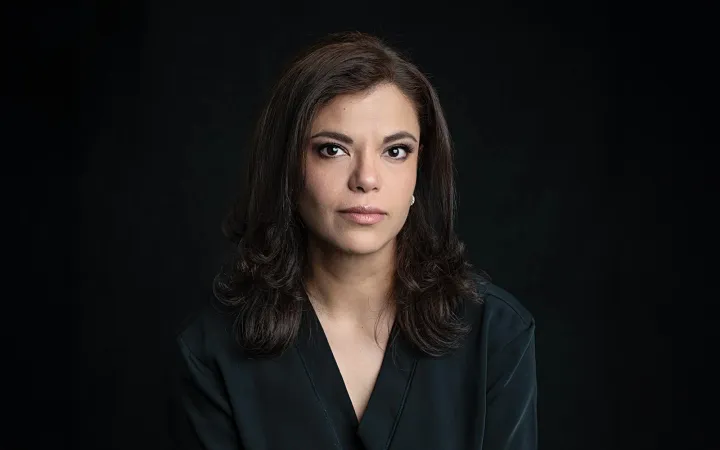

Por Linda Atach Zaga

“Si me matan, sacaré los brazos de la tumba y seré más fuerte”.

Minerva Mirabal, poco antes del 25 de noviembre de 1960, cuando su cuerpo y el de sus hermanas Patria y María Teresa, aparecieron destrozados en el interior de un vehículo arrojado al fondo de un barranco.

En sus inicios, el Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Violencia contra la Mujer, se instituyó con el fin de conmemorar la muerte de las hermanas Mirabal el 25 de noviembre de 1960 a manos de la policía secreta del dictador dominicano Rafael Leónidas Trujillo. Ahorcadas y apaleadas para que el asesinato pasara por un accidente de tránsito, las mujeres tenían entre 26 y 36 años cuando su feminicidio dejó huérfanos a cinco niños pequeños.

Con el tiempo, las repercusiones del suceso fueron mayúsculas, tanto, que entre las conclusiones del primer Congreso Feminista Latinoamericano y del Caribe, en 1981, surgió la propuesta reconocer el aniversario de la muerte de las Mirabal como una fecha para la denuncia y la conciencia de la violencia hacia las mujeres, misma que se oficializó a nivel mundial por la Asamblea General de las Naciones Unidas en 1999.

Si bien es imposible negar los avances desde que se nos permite exteriorizar y convocar a la reflexión y la sensibilización acerca de la violencia, la discriminación y la falta de equidad que nos cierran el camino, es importante recordar que hoy en México mueren más de 12 mujeres cada día y tan sólo en 2023 en el mundo fueron víctimas de feminicidio más de 50,000 mujeres, por el único hecho de serlo. Y lo más doloroso y digno de mención es que la mayoría de estas jóvenes, ancianas y niñas, fueron ultrajadas, ahorcadas o golpeadas hasta morir, por parejas y familiares más cercanos, porque es justo en los entornos más cercanos donde el infierno del maltrato se vuelve un mal irrefrenable.

Rumbo al trabajo, paso casi todos los días frente de la glorieta de las mujeres que luchan y cada vez que tengo la oportunidad, me acerco a leer las exigencias y consignas de las madres y buscadoras. Desbordadas a causa de la frustración que siente quien no es escuchado y atendido, las peticiones de las que lloran a sus muertas y desaparecidas resuenan de modo similar a las voces que denunciaron el asesinato de las Mirabal: “verdad y justicia”, “no a la impunidad” y el siempre presente “ni una más”.

Latentes de dolor, los escritos y dibujos de las hermanas, sobrinas e hijas de víctimas, nos hablan de la letal brecha que separa a las leyes de una sociedad que se niega a abrazarlas, de la naturalización de las agresiones y, sobre todo, de la educación machista y el tremendo retraso que implica:

¿Cuál es el futuro de una joven que quiere estudiar y superarse en un entorno que insiste en limitar y menospreciar su potencial? ¿Cuál es el futuro de las leyes al interior de una sociedad que se niega a abrazarlas e insiste en mantener su status quo?

¿De qué sirve que el delito del feminicidio ya cuente con una tipificación, si quienes imparten la justicia no lo hacen desde una perspectiva de género? ¿Hasta cuándo seguiremos tolerando que en nuestro país se desprecie de tal forma la mujer que su muerte se convierta en una cifra más?

Las preguntas son muchas más y muy pocas ofrecen una respuesta acorde a su gravedad. Quizá en estos tiempos de silencios y dudas sólo el arte sea capaz de contener y a la vez, dar cauce a tantísimo dolor y a las esperanzas que aún guardamos sobre la posibilidad de un futuro mejor.

En los últimos días tuve la fortuna de estar cerca de Elina Chauvet (Chihuahua,1959). Con un repertorio que transforma el enojo en un homenaje sensible que conmueve a quien tiene la oportunidad de verlo, esta arquitecta originaria de Casas Grandes incursionó por primera vez en el arte hace 15 años recopilado zapatos de mujeres, pintándolos de rojo y desplegándolos en las plazas públicas para exigir justicia y no impunidad por el feminicidio de su hermana en manos de su marido, pero también, para visibilizar la insostenible matanza de mujeres en Ciudad Juárez, que terminaron por propiciar la primera sentencia de Campo Algodonero emitida en noviembre de 2009 contra México por la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos.

En su última instalación, que podrá visitarse hasta el 15 de diciembre en el Museo Memoria y Tolerancia, Elina llama a la reflexión en los dieciséis días de activismo que siguen al Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Violencia contra la Mujer y así, materializada gracias al despliegue de más de cien pares de zapatos rojos que hablan de la muerte, pero también de la vida y gozo de las que alguna vez los usaron, en esta ocasión el lamento de Elina llega mucho más lejos al mencionar la insoportable y terrible práctica del feminicidio infantil, de la mano de un minúsculo par de botines de una niña no mayor de tres años.

Así, la pieza de Elina opera mejor y es más específica y clara que discursos y promesas. No habrá avance que sirva, ni ley que surta efecto mientras el feminicida acabe con la existencia de una mujer o niña sin consecuencias. El feminicidio no se lleva sólo a la víctima, sino que se expande a la familia, matando poco a poco a quienes lo sobreviven.

Ese debe ser el tema de hoy, es imposible hablar de otra cosa.

Las opiniones expresadas son responsabilidad de sus autoras y son absolutamente independientes a la postura y línea editorial de Opinión 51.

Comments ()