Por Diana Serros

A pesar de la incertidumbre política, económica y financiera tras el escalamiento del conflicto en Medio Oriente, hay noticias agradables en el ámbito económico. Por tercera vez en los últimos 54 años el Premio del Banco Central Sueco en Ciencias Económicas en memoria de Alfred Nobel se otorgó a una mujer, la doctora Claudia Goldin[1]. La profesora de la Universidad de Harvard fue galardonada por sus avances en la comprensión de la participación femenina en el mercado laboral, así como por brindar claridad sobre la dinámica salarial de las mujeres a lo largo de, por lo menos, dos siglos.

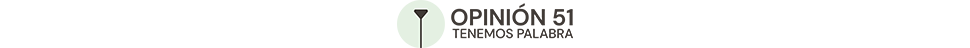

Hasta antes de las contribuciones de la Dra. Goldin—en la década de los ochenta y noventa—el consenso económico asumía la existencia de una relación positiva entre el crecimiento económico y la participación de las mujeres en el mercado laboral. Es decir, se creía que ante mayores tasas de crecimiento económico, la participación femenina en el mercado laboral también aumentaba. Sin embargo, tras la recolección—e incluso la corrección—de datos sobre participación laboral femenina en Estados Unidos durante los últimos 200 años, la Dra. Goldin desmintió dicha relación, argumentando que la participación histórica de las mujeres en la fuerza laboral podría describirse con una curva en forma de U.

En otras palabras, desde mediados del siglo XIX y hasta la década de los veinte, la participación de mujeres en el mercado laboral—particularmente, de las mujeres casadas—había presentado una tendencia descendente al pasar de, aproximadamente, 60% a cerca de 5%. Sin embargo, a partir de 1930 dicha tendencia se revirtió y, lentamente, la participación de las mujeres en el mercado laboral comenzó a ascender hasta llegar a poco menos de 60% en la última década.

La Dra. Goldin explicó este fenómeno exponiendo que, contrario al consenso económico y a la creencia popular, el trabajo femenino en el periodo preindustrial era más bien la norma: las mujeres ejercían tareas físicamente demandantes y equiparables con aquellas realizadas por los hombres, pues el consumo y la producción de bienes y servicios se llevaba a cabo dentro del núcleo familiar y en la propia comunidad. No obstante, hacia finales del siglo XIX y hasta la década de los veinte, las condiciones de trabajo se endurecieron de forma significativa, lo que culminó en estrictas legislaciones que limitaron tanto el número de horas trabajadas como la participación de las mujeres en actividades consideradas riesgosas. A partir de ese momento, el trabajo femenino estuvo limitado a las labores del hogar y el cuidado de los hijos. Además, la legislación y las ideas moralistas de la época incentivaron el concepto de que los hombres debían obtener mayores salarios, pues de ellos dependía el sustento familiar. No obstante, luego de fuertes disrupciones en el mercado laboral como resultado de la Gran Depresión y la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la proporción de mujeres en trabajos remunerados se incrementó de manera importante hasta llegar a poco menos de 60% en la última década. Este incremento fue una consecuencia directa de la introducción de la píldora anticonceptiva, de los avances tecnológicos, del impulso de la ideología y de las leyes feministas, de los estímulos en la educación y la salud femeninas y de la migración de las economías hacia las actividades terciarias (o servicios). En este sentido, Goldin señaló que, si bien las mujeres se habían incorporado de manera lenta pero exitosa en el mercado laboral, los salarios femeninos presentaban una diferencia significativa frente a los de sus contrapartes masculinas. De acuerdo con Goldin, esta dinámica salarial de género podía explicarse por dos factores: 1) ante la interrupción del trabajo remunerado tras el nacimiento del primer hijo y 2) luego de la migración hacia las actividades terciarias, pues éstas tendían a beneficiar a los empleados con alta disponibilidad “24/7” y con carreras largas e ininterrumpidas.

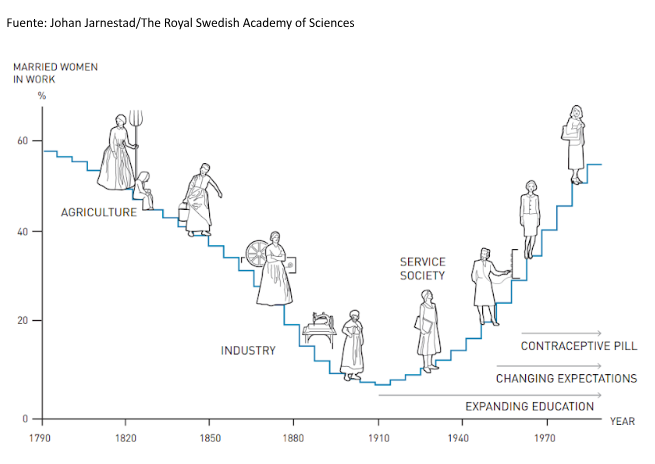

Sin duda, en México—y en el mundo—aún falta mucho por hacer. Si las mujeres no tienen las mismas oportunidades de participar en el mercado laboral, o participan en condiciones desiguales, la asignación de capital humano en la economía se torna ineficiente. En otras palabras, es económicamente ineficaz que los empleos no recaigan en la persona más calificada y, si el salario difiere por realizar el mismo trabajo, las mujeres pueden verse desincentivadas para trabajar y tener una carrera. En este sentido y de acuerdo con estudios de McKinsey & Company “la tasa de participación laboral de las mujeres en México sigue siendo una de las más bajas de América Latina” (Bolio, Ibarra, Garza, Rentería, & De Urioste, 2022). Además, este reporte muestra que sólo una de cada 10 mujeres llega a puestos de dirección general (C-suite).

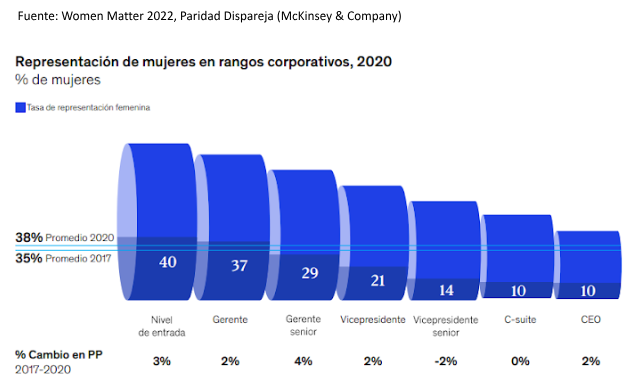

Este reporte también exhibe que las diferencias salariales entre hombres y mujeres en México son, desafortunadamente, brutales. En los rangos de entrada, las mujeres ganan, aproximadamente, 7% menos que los hombres. Sin embargo, en los niveles directivos, la diferencia es de cerca de 17%. Estas cifras son consistentes con las conclusiones de la Dra. Goldin, pues para las mujeres no sólo es más difícil alcanzar puestos altos, sino que además, reportan salarios más bajos.

En suma, los resultados de la Dra. Goldin son altamente significativos, pues, por un lado, explican las deficiencias en la participación femenina en el mercado laboral y, por otro, ponen en evidencia el impacto social del trabajo femenino, las carencias en el diseño de incentivos para reducir la brecha salarial de género, la importancia del apoyo entre mujeres y la falta de políticas públicas para promover la participación de las mujeres en el mercado laboral—especialmente en países en vías de desarrollo.

[1] Anteriormente, este premio lo recibieron las doctoras Elinor Ostrom (2009) y Esther Duflo (2019) por sus investigaciones en torno a la sobreexplotación de recursos naturales colectivos y por las aportaciones en el análisis y combate de la pobreza global, respectivamente. Sin embargo, ambas compartieron el premio con colaboradores varones.

Trabajos citados

Bolio, E., Ibarra, V., Garza, G., Rentería, M., & De Urioste, L. (Agosto de 2022). Women Matter Mexico 2022. Obtenido de https://womenmattermx.com/

Perfil profesional

*Maestra en Finanzas y Licenciada en Economía por el Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey con más de 13 años de experiencia en análisis macroeconómico y de mercados, gestión de inversiones, métodos cuantitativos y administración de riesgos.

Las opiniones expresadas son responsabilidad de sus autoras y son absolutamente independientes a la postura y línea editorial de Opinión 51.

Más de 150 opiniones a través de 100 columnistas te esperan por menos de un libro al mes.

Comments ()