Por Claudia Ocaranza

El presupuesto para el Instituto Nacional de la Economía Social, responsable de implementar y operar las estrategias para el desarrollo del cooperativismo en México, ha caído 88% en los cinco años de la administración del presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador. El tratamiento del cooperativismo, insertado en políticas sociales cercanas al populismo, hace que el movimiento no sea impulsado como la base hacia una economía más democrática y justa. Diferentes estados del país tienen programas de apoyo a las cooperativas y organizaciones sociales; sin embargo, falta un registro nacional de cooperativas, pues quedó descartado en la publicación en 2012 de la Ley de la Economía Social y Solidaria y también en su última modificación en 2019. Mientras tanto, López Obrador impulsa al movimiento cooperativista en las regiones donde resulta conveniente para sus megaproyectos, como en Quintana Roo con el Tren Maya.

Por Claudia Ocaranza, con información de Santiago Ancheita / Periodismo Empower

“Nosotros sí apoyamos al cooperativismo”, dijo el presidente mexicano Andrés Manuel López Obrador en su conferencia de prensa del 27 de febrero de 2019 en respuesta a una pregunta de un reportero sobre cómo sería integrado el cooperativismo en su proyecto económico[1]. A pesar de la declaración de López Obrador, ese año el presupuesto del Instituto Nacional de la Economía Social (INAES), órgano desconcentrado de la Secretaría de Bienestar que tiene el mandato de impulsar la economía social y solidaria, fue recortado casi 70% en comparación con 2018. Pasó de tener 1,979,206,256 pesos anuales a sólo 629,362,530 pesos. La caída no ha parado; para 2023 el presupuesto es de apenas 229,486,008 pesos.

Expertas y expertos entrevistados por Empower aseguran que el menor presupuesto del INAES se debe, además de a la austeridad promovida por el Presidente, a un cambio de estrategia que incluye romper lazos con el corporativismo y el sindicalismo a modo. Sin embargo, una ley ambigua, la falta de un registro nacional de cooperativas, las diferencias regionales y la falta de comprensión profunda del cooperativismo provocan que en México todavía se le vea como un factor de política social y no como la base para impulsar una economía más democrática y justa.

A decir de Eduardo Enrique Aguilar, cooperativista y profesor investigador de la Universidad de Monterrey, con el cambio de la Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (Sedesol) a la Secretaría de Bienestar sucedió un traspase de fondos que “sigue una estructura corporativa pero desde otra óptica, ya no desde lo que sería una caja chica como lo era antes el INAES”.

La nueva estrategia se basa en alianzas con organismos como la Confederación Alemana de Cooperativas (DGRV) y la Cooperación Alemana al Desarrollo Sustentable (GIZ)[2], y en programas a nivel nacional con gobiernos locales, como lo son los Nodos de Impulso a la Economía Social y Solidaria (NODESS), “una red de alianzas territoriales conformadas por al menos tres actores diferentes: instituciones académicas, gobiernos locales y Organismos del Sector Social de la Economía (OSSE)”, según el INAES[3].

Aún así, “no hace sentido el recorte del 70% al INAES porque no es que el sector social de la economía para su desarrollo no necesite de capital, recursos o una serie de apoyos. Lo necesita, por supuesto, y lo que hacen es desfondar el Instituto que estaba destinado para eso. Históricamente se fortalece el sector privado porque tiene un sector gubernamental de respaldo suficientemente fuerte y con recursos que constantemente están inyectando al sector privado”, dijo Aguilar, también doctor en Economía Política del Desarrollo, en entrevista con Empower.

Sin registro nacional de cooperativas

Con la inauguración de María Luisa Albores como secretaria de Bienestar desde el inicio de la administración de López Obrador, llegó una corriente del movimiento cooperativista que en otros países ha tenido éxito. Se trata de la corriente española, encabezada por la Corporación Mondragón en España. Juan Manuel Martínez Louvier, el director general del INAES, estudió su maestría en gestión de empresas cooperativas en Mondragon Unibertsitatea[4]. Ambos nombramientos generaron expectativa e ilusión entre quienes han estudiado e impulsado un cambio hacia una economía social y solidaria.

Al nombramiento del Consejo Consultivo de Fomento a la Economía Social y Solidaria 2019-2024 del INAES asistieron, además de Albores y Martínez Louvier, personajes relacionados al cooperativismo, como Héctor Valdés Trejo, cooperativista; César Escalona Fabila, coordinador general de planeación y evaluación del INAES; María Luisa de la Garza, doctora en filosofía; y J. Sabás Ledesma Jaime, gerente general de Caja Popular Las Huastecas[5].

Sin embargo, cuatro años después, el INAES no ha publicado en su sitio web quiénes conforman dicho consejo actualmente. De acuerdo con Miguel Torres Cruzaley, especialista en economía solidaria por la Escuela Andaluza de Economía Solidaria, “con los cambios y recortes, muchos de esos integrantes se echaron para atrás”, dijo en entrevista con Empower.

La última evaluación del Programa de Fomento a la Economía Social (PFES), operado por el INAES para “fortalecer las capacidades y los medios de los Organismos del Sector Social de la Economía (OSSE)”, se hizo en 2019-20 por el Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL)[6], en la que se encontró que en 2019 el programa apoyó a 2,539 OSSE, “80% menos OSSE que en 2018”. Una de las causas definidas por el CONEVAL fue la reducción en el presupuesto del INAES. El artículo 52 de la Ley de la Economía Social y Solidaria marca que debe haber una evaluación del cumplimiento de la misma cada tres años. Aunque existen auditorías de la Auditoría Superior de la Federación (ASF) de años anteriores, no hay auditorías de 2020 en adelante.

Para Aguilar, autor del libro “Co-laboramos. Manual sobre cooperativas”, el problema surge en el origen de dicha ley, creada en 2012, que dejó fuera la demanda social sobre la necesidad de tener un registro nacional de cooperativas. La Ley fue modificada en 2015 y 2019, pero no se incluyó la creación del registro.

“El sentido de la Ley es el de cooptación, de poder controlar un sector más en términos de lo que hace el Estado. Pero está tan mal hecha que ni eso lo termina de representar porque es extremadamente ambigua”, dijo Aguilar.

Torres Cruzaley agrega que el primer descalabro de la Ley fue cuando pasó de ser responsabilidad de la Secretaría de Economía, como era desde su promulgación[7], a ser de la Sedesol, lo cual sumó a que en México se tenga “una visión más social que económica del cooperativismo” y que se mantiene actualmente.

La Ley también marca la existencia de un Observatorio del Sector Social de la Economía, promovido por el INAES, pero en su página se encuentran pocas referencias al mismo y la página oficial envía a una sitio de pueblos mágicos[8].

Cooperativismo al servicio de la agenda presidencial

Así como no existe un registro nacional de cooperativas, tampoco existe una única forma de ejercer el movimiento en el país. Sin embargo, las personas entrevistadas para este reportaje coinciden en que los aprendizajes estatales no se traducen en acciones a nivel nacional.

“A pesar de esa historia tan rica que existe a nivel local en muchos sitios del país, no permea y no salen de sus nichos, y falta un reconocimiento de eso a nivel federal”, dijo a Empower Carolina Maldonado, experta en género, desarrollo y economía por el Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México (ITAM) y la Universidad de Sussex.

Para Maldonado, el poco reconocimiento del cooperativismo como movimiento económico por parte del gobierno actual se refleja también en cómo otorga los apoyos económicos la administración de López Obrador.

“Hay incompatibilidad entre cómo se entregan los programas sociales y una visión cooperativista. La visión de los apoyos individuales busca que cada quien lo resuelva de forma individual, con el apoyo de madre soltera le pagas a las abuelitas, como dijo AMLO. Y ésa es una visión que no va con el cooperativismo”, dijo Maldonado.

De acuerdo con Torres Cruzaley, el lugar que tiene el cooperativismo en la administración actual gravita en su utilidad para los objetivos y megaproyectos de López Obrador.

Los ejemplos existen. El INAES y la Subsecretaría de Inclusión Productiva y Desarrollo Rural colaboran en la “Estrategia de Redes de Valor” del programa Sembrando Vida mediante acciones “en materia de Economía Social y Solidaria (…) para fortalecer las capacidades organizativas y empresariales de las y los sembradores”[9].

“Los beneficiarios de Sembrando Vida reciben una cantidad mensual y otro poco se va a un guardado que se tiene que usar en beneficio social, pero tampoco hay mucho acompañamiento de eso. Se genera una nueva estructura o red pero condicionada a participar en el programa. Eso no necesariamente genera organizaciones sólidas. Y tampoco responde a cómo se vende lo que sale de las cooperativas o cuáles son las conexiones con los distintos mercados”, explicó Torres Cruzaley.

En enero de este año, López Obrador recibió a integrantes de la Unión de Cooperativas Tosepan, Puebla, ligada a la actual secretaria de Medio Ambiente, María Luisa Albores[10], que fue quien instauró la nueva estrategia de economía social en Bienestar entre el 1 de diciembre de 2018 y el 2 de septiembre de 2020.

En mayo, el Presidente invitó a su conferencia diaria a Mara Lezama, gobernadora de Quintana Roo, quien anunció un nuevo plan de apoyo a cooperativas en aquel estado, donde pasará el Tramo 4 del Tren Maya. “El efecto multiplicador en beneficios del Tren Maya nos encaminó a crear este modelo, porque debemos darle apoyo y seguimiento a todo el crecimiento económico que seguirá surgiendo a las nuevas ideas, a los nuevos modelos de negocio y, en general, a las nuevas oportunidades para alcanzar el bienestar social”, dijo Lezama[11].

El INAES no respondió a las solicitudes de entrevista ni a las preguntas enviadas antes del cierre de este reportaje.

El Caso CDMX: números y montos sin coincidir

Aunque de acuerdo con las personas expertas entrevistadas por Empower el programa de Economía Social de la Secretaría del Trabajo y Fomento al Empleo (STyFE) de la Ciudad de México es uno de los que más trabajan con las comunidades de base, al dividirse en tres subprogramas para la creación y fortalecimiento de las cooperativas los retos se mantienen.

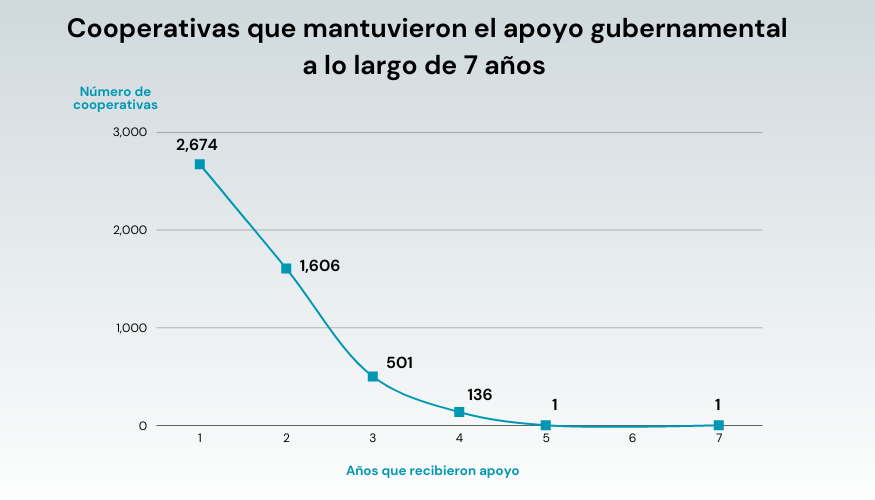

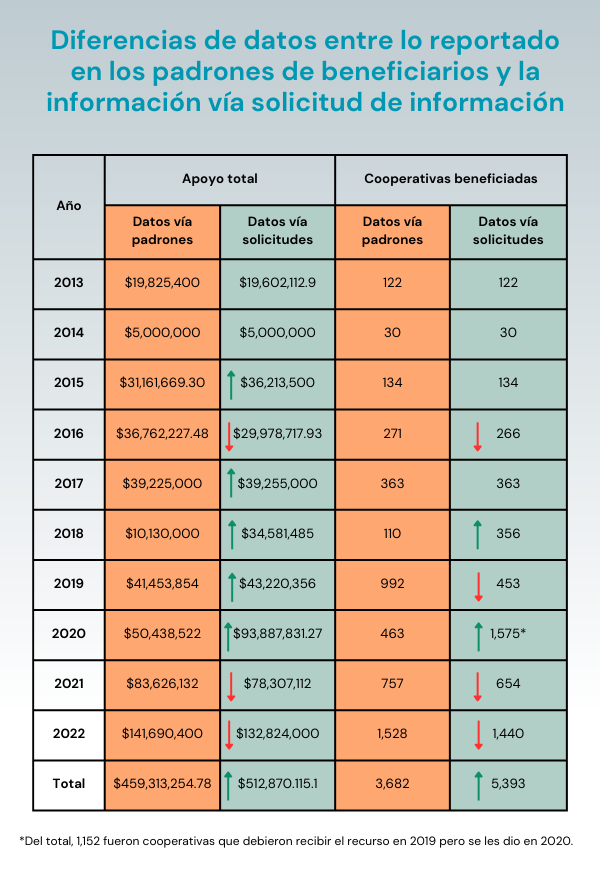

Año con año el programa aumentó su presupuesto para llegar a más cooperativas y organizaciones sociales. Entre 2013 y 2022, 3,682 cooperativas recibieron 459,313,254.78 pesos del programa, de acuerdo con datos obtenidos vía solicitudes de información y analizados para este reportaje. Pero sólo una cooperativa recibió apoyos durante siete años, alcanzando un monto de 1,040,506.94 pesos en total.

La mayoría de las cooperativas (2,674) sólo recibió alguna cantidad económica durante un año. Mientras tanto, la cantidad de cooperativas beneficiarias que repitieron el acceso al apoyo por varios años cayó considerablemente (1,606 recibieron el recurso por dos años y sólo 501 por tres años).

En 2023, la STyFE publicó en la Gaceta Oficial que el programa destinaría 140 millones de pesos a 770 cooperativas a través de los subprogramas de impulso, creación y fortalecimiento[12]. Sin embargo, en una respuesta a una solicitud de información[13] presentada por Empower, la Secretaría respondió textualmente que, para 2023, “aún no se tiene ninguna cooperativa beneficiaria del programa”, mientras que el recuadro que acompaña la respuesta, marca “En proceso” para 2023.

Incluso, los montos totales de apoyos económicos por año y el número de cooperativas apoyadas no coinciden entre lo que se reporta en los padrones de beneficiarios y lo que la STyFE respondió en solicitudes de información.

El caso de mayor disparidad es 2018 cuando, según el análisis de datos realizado por Empower a partir del padrón del programa, la STyFE repartió 10,130,000 pesos entre 110 cooperativas. Pero la misma secretaría respondió vía solicitudes de información que ese año apoyó a 356 cooperativas con un total de 43,581,485 pesos.

Para Aguilar, la discrepancia en los datos abona a la necesidad de un registro nacional de cooperativas.

La STyFE no respondió a las solicitudes de entrevista ni a las preguntas enviadas antes del cierre de este reportaje.

Con las cooperativas no alcanza

Traditionally, la constitución de cooperativas ha sido una solución para que una familia acceda a ayudas económicas para su negocio familiar, sin que eso signifique que, de facto, el negocio funcione como una cooperativa, es decir, de una forma horizontal y con una repartición igualitaria de las ganancias. La misma Ley de Economía Social nombra como sujetos de la ley a figuras que no son cooperativas, como ejidos y comunidades.

“Resulta una ley genérica que, al permitir que todo entre, infla los números en cuanto a cooperativas”, explica Torres Cruzaley.

En 2019, 59% de 686 personas representantes de cooperativas respondió a un censo realizado por la empresa Parametría, facilitada a Empower por la STyFE vía una solicitud de información, que la razón para iniciar una cooperativa fue que “un familiar reunió a otros miembros de la familia”[14].

Según ese estudio, las cooperativas encuestadas ingresaron en promedio 20,070 pesos mensuales, lo que significó un ingreso mensual por socio de 5,358 pesos. La mayoría de los encuestados pertenecía a una cooperativa con cinco socios y un ingreso promedio mensual de 19,134 pesos. Es decir, la mayoría ganó 3,827 pesos al mes, apenas por encima de los 3,139.20 pesos que era el salario mínimo mensual en 2019[15].

Con esos datos, 23% de los encuestados refirieron que “no les alcanza para pagar deudas y/o créditos y mantenerse”, mientras que otro 23% respondió que les alcanza “justo”.

Los expertos y la experta entrevistada coinciden en la necesidad de transitar de una visión del cooperativismo como una política social hacia una que lo incluya como base del desarrollo económico del país, para incluso aspirar a que se creen cooperativas de los sectores grandes de la economía y no sólo del tercer sector.

“Es muy delgada la línea entre que sean cooperativas independientes y que dependan de acompañamiento externo o recursos externos, pero las cooperativas siempre requieren acompañamiento de largo aliento. Un año no es nada. Es necesario que las integrantes puedan ir aprendiendo en el tiempo qué pasa para enfrentar y resolver los conflictos y la toma de decisiones”, dijo Maldonado.

Para la especialista en género, impulsar el cooperativismo desde un modelo económico y dotarlo de fondos suficientes generarían también una mayor oportunidad de desarrollo para las mujeres, quienes encuentran problemas para integrarse a un empleo formal al ser las responsables de los cuidados familiares y el sostén económico, por lo que muchas optan por crear cooperativas que les permitan trabajar y efectuar labores de cuidado de forma colectiva.

Desde hace años, colectivos, organismos internacionales, organizaciones ciudadanas, cooperativas y uniones de cooperativas se han pronunciado por impulsar un modelo de economía social para contrarrestar los efectos del capitalismo voraz y como alternativa en la forma de vida y organización. Simel Esim, jefa del Servicio de Cooperativas de la Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT), declaró que la economía social y solidaria “ha ganado reconocimiento por su rol en crear y sostener trabajos y proveer servicios para miembros, usuarios y comunidades durante la pandemia por COVID-19. En un momento en que el llamado por nuevas formas de hacer negocios está creciendo, la economía social y solidaria puede proveer una base para un modelo de empresas que impulsa la inclusión, la sostenibilidad y la resiliencia”[16].

Referencias:

[4] “Juan Manuel Martínez Louvier”, LinkedIn, consultado en julio 2023.

[8] “Osse”, consultado en julio 2023.

[9] “Estrategia INAES-Sembrando Vida”, INAES, 31 agosto 2022.

[12] “CDMX destinará 140 millones de pesos para 770 cooperativas”, La cooperacha, 13 enero 2023.

[13] Folio 090163523000255, 9 mayo 2023.

[14] “Censo de empresas sociales y solidarias de la Ciudad de México”, Parametría, diciembre 2019.

[16] “Interview with Simel Esim on ILO’s Latest Report”, Sosyal Ekonomi, 4 mayo 2022.

Las opiniones expresadas son responsabilidad de sus autoras y son absolutamente independientes a la postura y línea editorial de Opinión 51.

Más de 150 opiniones a través de 100 columnistas te esperan por menos de un libro al mes.

Comments ()